- Gomendio has substantial expertise as a government counselor on evidence-based policy.

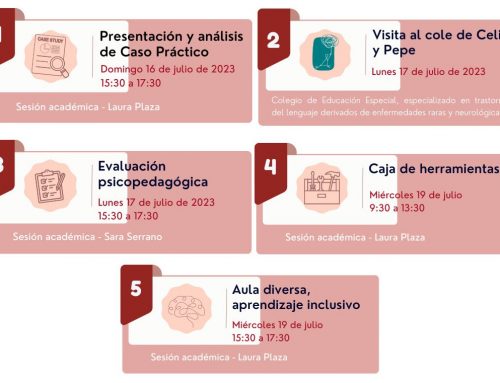

- She attended the Fundación Querer’s IV Neuroscientific and Educational Conference.

- “Students with disabilities need a different approach; this is equal opportunity”

More than 228,000 students in Spain have very diverse educational demands caused by a disability or by a significant disorder (intellectual, motor, sensory, etc.). As a result, depending on their unique characteristics, kids must be enrolled in either regular classrooms or special educational schools.

We must diversify for this type of learner in order to maximize their potential: “Equality of opportunity consists of diversifying and providing each student with the support, reinforcement, and type of learning that best fits their needs and aptitudes.” This is what Montserrat Gomendio Kindelán, former Secretary of State for Education, Vocational Training, and Universities between 2012 and 2015, and former Deputy Director of Education at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), who has extensive experience advising national governments on evidence-based policies, believes.

She is currently a professor at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and a visiting professor at University College London’s Institute of Education. Gomendio also attended the Fundación Querer’s IV Neuroscientific and Educational Conference, specifically one of its panels on the importance of scientific research in special education policies.

Question: You began your professional career in biology and scientific research before focusing on education. What prompted you to change your mind and pursue a career in education?

Answer: My academic background led me to strive to understand the world using solid, objective evidence. I spent a lot of time doing research in evolutionary biology, which is not a close field, but I was interested in taking a new approach to education than what had been done before: trying to base educational practices on evidence. To determine what worked in similar situations and, as a result, which policies based on that data were most likely to have a good influence on our country. At the time, there was a widespread belief that there was little evidence that could guide educational decisions, and that they were more ideological in nature.

Q: Do you believe, based on your experience, that scientific evidence is increasingly being incorporated when formulating educational policies, particularly for children with special educational needs?

A: More and more people say that the policies they support are supported by evidence, but I disagree. Making evidence-based policies was still unusual about ten years ago. Nowadays, almost everyone claims that their policies are evidence-based before suggesting policies that they feel will be more effective. However, a little research reveals that this is not the case; they are based on highly questionable evidence, with inadequate data and analysis. Attempts are frequently tried to simulate policies that have worked in completely different contexts, and so adopting them here would have very detrimental consequences, as is the case with Finland and its inclusive approach.

«Finland’s setting is considerably different from ours, and the evidence that these policies have had a favorable impact is more than debatable.”

Q: What is the problem with Finland’s educational system? Is it a model to consider?

R: People assume that Finland is still a success today, and it was, but only at one point in time: in the year 2000, when PISA began, Finlandia had exceedingly high reading scores. Furthermore, it was the first PISA cycle, with a very small and homogeneous set of countries participating. Finlandia’s results began to decline in 2000 and have not stopped since. We must also remember that Finland had a highly homogeneous and uniform population at the time, with families usually taking on the job of teaching children to read before they attended compulsory schooling. Finland’s context is considerably different from ours. Furthermore, there is little evidence that these policies have had a favorable impact.

Q: Why does this approach not work in Spain?

R: Spain’s society is far more diversified, with far more different students and an adult population with lower levels of knowledge and skills than Finland. Despite this, we have imitated these policies in Spain, and they have even been taken to extremes, although they have not been copied in Finland or any other Nordic country. Spain tries to implement these inclusive policies, which include having all students in the same classroom without making divisions based on level of performance, classes, or groups, with the understanding that this inclusivity is the only way to achieve equity, but these policies were implemented in Finland ten years ago, and even if they have been maintained, Finland has been declining.

“Data speak for themselves, so you just have to know how to distinguish between robust and solid evidence and something purely ideological.”

Q: So why do they apply them?

R: The question of inclusion is based on a qualitative comparison rather than a quantitative examination. Because the Nordic countries are equitable and adopt inclusive policies, the idea is that the way to attain equality is through inclusion. The difficulty with this line of reasoning is that it is most likely the other way around: in a society that has been quite egalitarian for a long time, such as the Nordic one, you can afford to implement inclusive policies since your student population is very homogeneous. However, when such policies are applied to nations that have not achieved those levels of equity, such as Spain, the model lacks any lever to manage diversity, resulting in mediocrity in the system and, most importantly, leaving all impaired students out of the equation.

Q: Is there evidence to demonstrate the efficacy of these inclusive strategies in Spain?

A: No, in Spain, we still have a system that is utterly blind to the impact of educational policies: we do not have our own evaluation systems, which is a major irresponsibility and an absolute exception on the international stage.

“Students with disabilities need different treatment, that is equal opportunities.”

Q: What occurred in other countries that used this model?

R: It depends on the setting, but I’ll take Portugal as an example because its student and adult populations are quite diverse, similar to those in Spain. Portugal, like us, began by establishing inclusive policies, but it did not succeed. In all worldwide comparisons, it likewise had an extremely high dropout rate and mediocre results. They introduced measures very similar to our LOMCE in 2015, building systems to manage student diversity; they improved significantly in all comparisons, and there was a substantial decrease in educational dropout to 6%; Spain is at 13. However, an administration arose that, from an ideological standpoint, believed that it was vital to return to inclusion, and the country suffered yet another setback. Because the data is available, it is critical to discern evidence from just ideological claims.

Q: You were an advocate of the LOMCE as Secretary of State for Education, Vocational Training, and Universities. What are your thoughts on LOMLOE’s commitment to “inclusion,” in which children with special needs are “integrated” into regular education centers?

R: The issue with LOMLOE is that equity is designated as a priority, despite the fact that equity is just as vital as quality. Understanding the concept of inclusion, on the other hand, as “if we give the same treatment to all students, they all have the same equal opportunities”… This is not true! These children have a condition that causes them to study in a different rhythm and approach than other kids. As a result, putting them in the same class with the same teacher and curriculum is ultimately a form of exclusion because their very specific needs are not being addressed to or even acknowledged. You are not only not providing them with equal possibilities, but you are also not providing them with the opportunity to learn and develop to their greatest potential. These children must be treated differently, and this is where true equality of opportunity rests. This strategy was taken by the LOMCE, which consists of diversifying and providing each student with the assistance, reinforcement, and type of learning that best suits their needs and skills.

«Seating them in the same class with the same teacher and curriculum is, in the end, a form of exclusion for them.»

Q: On the other hand, do you believe our traditional educational system is capable of dealing with such diversity? Are there enough resources?

A: There are currently insufficient resources for regular schools to accept a percentage of these children and provide them with the attention they require. Furthermore, there is a question of effectiveness: with the few resources we have, is it really the most effective thing for all schools to have some children with special needs who require specialized teachers? Or is it better to put them in a specific center where you can concentrate all of the resources and achieve much higher efficiency because all of the professors will be specialized and the resources you require will be available to many students? It is unrealistic, and, more importantly, I am unaware of any economic impact plan that defines the increase in resources required to make this happen.

Q: So, where should the education of children with special educational needs go?

A: I believe it depends on the child’s level of disability: some can be integrated and not necessarily be in a special educational school, or not throughout their entire lifeschool; and others whose disability affects their learning capacity much more and they may need to be in a special educational school. When the student body is diverse and the adult population has a low level of knowledge and abilities, the educational system must be adaptable and offer diversity. Children with special needs are at the extremities of this spectrum, thus they require specific attention.